What could happen if the UK lost RED II recognition?

Thursday, 20 June 2024

Presently, under the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), UK-grown wheat is one of many biofuel feedstocks which can be used to supply biofuel into the EU. However, the UK could soon lose its recognition under RED II.

Biofuel production in the UK predominantly occurs at the UK’s two main bioethanol plants Ensus and Vivergo, both situated along the northeastern coastline in England, where domestically produced wheat and imported maize are used for biofuel production.

In June 2023, the European Commission announced that it would no longer recognise the national accreditation body which assesses the assurance schemes (e.g. TASCC (AIC), RTA, SQC) which assure growers in the UK so they can supply wheat for biofuel production. While assurance schemes remain able to assure growers for RED II access, the European Commission is expected to announce how the recognition will be implemented by 01 January 2025.

In addition, the UK is required to review the classifications of NUTS 2 regional values which are codes that represent particular regional areas for the application of regional policies. The use of NUTS 2 codes for RED II helps to improve the efficiency of measuring biofuel production in the identified areas, and therefore supports inclusion under the policy.

Considerable work has been undertaken and resource invested by assurance schemes and industry so that UK growers currently remain able to supply relevant biofuel feedstock under RED II, a market which offers significant support to the UK arable sector and wider agricultural industry.

What has happened to the UK’s involvement with RED II

At the turn of the new year (2024), the UK was due to be unable to use domestically produced crops, such as wheat, as a feedstock for biofuels under RED II following the UK’s exit from the EU. However, in December 2023, the European Commission postponed this deadline in response to the feedback it had received regarding the situation. Therefore, currently until 2025, the UK is still eligible to supply wheat as a feedstock for biofuel which is compliant under RED II.

Further to this, there is a requirement to ensure that UK greenhouse gas emission data on a NUTS 2 regional basis is approved prior to harvest 2024 to allow this year’s harvest to be used in biofuel production. Presently, the reclassified NUTS 2 codes have been submitted to the European Commission for recognition which is understood to be in process.

There is also the implementation of the EU Union Database for Biofuels to consider. This requires all feedstocks used in biofuel production to be traceable and logged from November. If either of the above are not resolved, then domestically produced feedstocks would not be able to enter the biofuel market under RED II.

Also, within the revisions to RED II in 2018, the implementing regulations were changed such that voluntary assurance schemes were required to re-apply for recognition as well as potentially undertake a review of their respective scheme; both requiring time before recognition from the European Commission could be granted.

Whilst a short-term fix has been allowed to keep the UK supply chain open, there remain longer-term risks in play.

What role does UK biofuel production play within the UK wheat sector

The usage of feedstocks from Ensus and Vivergo can influence the national human and industrial consumption of wheat which feeds into the AHDB’s UK cereals supply and demand. Therefore, the usage of wheat from these two respective plants alone can impact the season ending stocks for wheat. Ensus and Vivergo both have the capacity to process circa 1 million tonnes of feed grains each per year. While Ensus has the ability to process both wheat and maize, Vivergo can currently only use wheat.

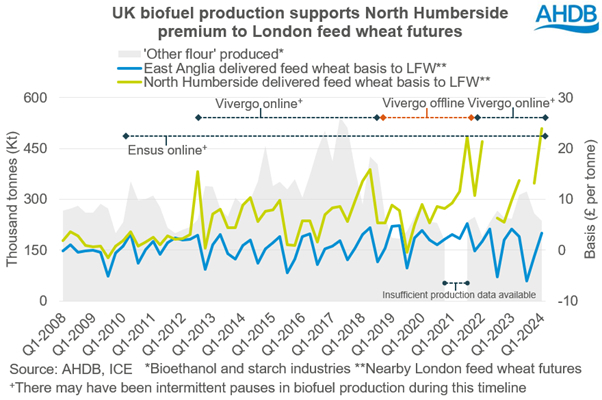

There is no publicly available data to show exactly how much cereals the UK bioethanol sector solely uses. However, the volume used is incorporated with flour millers’ usage in the UK Flour Millers usage data. Bioethanol production is included under 'Other flour’ production alongside starch for human and industrial consumption. The 'Other flour' category can be used to broadly assess usage by the bioethanol industry.

When both bioethanol plants were at peak production, in the 2016/17 marketing year, 1.9 Mt of ‘Other flour’ was produced over the season, 34% of total flour produced for that period. In comparison, when Vivergo went offline in October 2018 for nearly three and a half years, ‘Other flour’ production for 2018/19 was 0.9 Mt less than 2016/17 at 1.0 Mt, accounting for 21% of total flour production. While Ensus was largely in operation during Vivergo’s offline period, it began to use more imported maize to produce bioethanol due to its performance and relative price to domestic wheat at the time. After three marketing years of consecutive falls for ‘Other flour’ production, in 2021/22, production increased, likely supported by Vivergo returning online during this period.

How could the loss of access to RED II impact the UK cereals sector

If UK-grown wheat could no longer be used as a biofuel feedstock to access the EU biofuels market under RED II, this will likely weigh on the domestic cereals balance. With such large demand centres taken offline for the domestic market, in typical production years, the UK market would have a larger surplus of grain to export or store. It is also important to note that the wheat supplied is typically of feed wheat quality. Therefore, demand from the UK biofuels sector helps to support the price of domestically produced feed wheat which can be more ample in supply than milling wheat.

Biofuel production can be seen to have an impact on delivered prices into North Humberside, highlighting the strength of demand this sector has within the domestic market.

While Ensus began production in February 2010, the establishment of Vivergo (where wheat is the predominant feedstock) in 2012 bolstered biofuel production along the northeastern coastline, and with it feed wheat demand. In comparison with East Anglian feed wheat, North Humberside delivery began to demand a stronger premium to UK feed wheat futures in 2012.

Subsequently, the temporary cease of operation by Vivergo in late 2018 looks to have then weighed on the premium. Then, when the UK government implemented policies in 2021 which supported the biofuels sector (such as granting E10 petrol), the premium of feed wheat delivery into North Humberside rose significantly as this pronouncement supported Vivergo’s decision to come back online. Evidently, other regional supply and demand factors will come into play, but the existence of these two demand points in the north of England has amplified the regional differences.

Therefore, if all domestic demand for UK-grown feed wheat remained the same except for the loss from biofuel demand, then feed wheat could need to trade at an export parity in years of a larger domestic crop. Export markets are considerably influenced by the supply of grain in major exporters, where the Black Sea region holds a strong competitive advantage. So, in order to compete, it is probable that UK feed wheat would depreciate in price. Since 2010, as a percentage of production, exports were greatest in the calendar year of 2010 at 22% and the lowest in 2021 at 2%. Over the same period, the lowest price for feed wheat was in 2010 (calendar year) at £113/t, and the third highest price was in 2021 at £191/t, third to 2022 and 2023. The pressure on the feed wheat price as a result of greater exportable surpluses can also be seen in the futures market, where nearby London feed wheat futures prices lower than nearby Paris milling wheat futures during times of greater UK wheat export pace.

In addition, recent analysis looking at the cost of wheat production across key global wheat exporters highlights how challenging it could be for the UK to price competitively for exports while also ensuring growers a profitable margin. Of the countries reviewed, Denmark was the only country in the analysis which had a higher cost of production than the UK, while key wheat exporters such as France, Ukraine, and the US all had considerably lower costs of production.

So trading at export parity could amplify pressure on the arable sector, which is already adapting to the changes in domestic agricultural policy.

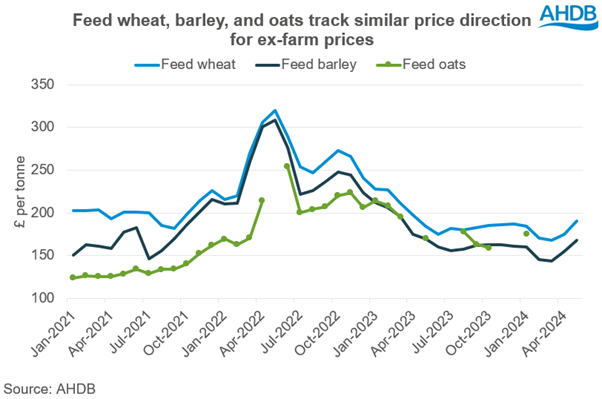

Moreover, if wheat prices were to depreciate as a result of surplus supply due to the loss of the biofuel demand, this could then also pressure feed barley and feed oats prices which tend to track the price of feed wheat closely. If feed wheat loses value, feed barley and feed oats may also lose value in order to retain competitiveness and market share in the livestock feed ration. So, while this could benefit the livestock sector with lower feed costs, the knock-on impact of increased price competitiveness across cereal feed crops may not only pressure the profit margin for feed wheat.

Wider UK agriculture

In addition to offering demand for UK wheat growers, Ensus and Vivergo also produce protein enriched dried distillers’ grains (DDGs) as a byproduct from biofuel production which is offered to livestock farms domestically. Therefore, while biofuel production in the UK may continue regardless of the outcome of RED II, if biofuel access under RED II was lost and this led to a pause in biofuel production, this will then impact the production of DDGs and therefore the availability, range, and competition of livestock feed within the region.

Key takeaways

RED II

For the continuity of using UK-produced biofuel feedstocks under RED II, the NUTS 2 codes would need to be approved by the European Commission by harvest 2024, the EU Union Database for Biofuels would need to be implemented by November 2024, and then the European Commission would need to approve the accreditation of assurance schemes by 01 January 2025 so assurance schemes can continue to assure growers to supply RED II compliant biofuel feedstocks.

Potential impact on UK agriculture

While domestic wheat prices are, and will continue to be, influenced significantly by the global wheat markets and supply balance, the loss of access for UK-grown wheat to be used as a biofuel feedstock under RED II is likely to weigh on domestic cash prices. This is evidently a longer-term view away from the season specific issues that we see from lower planting for harvest ’24.

The volume of wheat that is used by Ensus and Vivergo is a considerable amount relative to the UK’s production and, with the exception of temporary pauses in production, the all-year-round demand supports domestic price competitiveness throughout the year.

The potential transition from usually trading at an import parity to export parity in response to greater domestic feed wheat availability would likely lead to a depreciation in cash values for export competitiveness, which could pressure net margins on feed wheat production. Pressure on the price of feed wheat may ripple throughout the domestic feed cereals market, where feed barley and feed oats may also lose value to maintain market share in the livestock feed ration.

In addition, it is likely that the milling wheat premium could widen in response to a potential depreciation of domestic feed wheat prices. Should the premium extend, this may heighten the importance of achieving milling wheat specification when growing milling wheat varieties.

Furthermore, if the consequential market challenges led to a pausing of biofuel production in the UK, the supply of DDGs for livestock businesses within the region could contract. Presently, the supply of DDGs as a byproduct from biofuel production improves the availability, and therefore competition, of livestock feed with region.

In 2009, the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) was established by the European Commission, and in 2018, revisions were made to the policy which led to RED II. Under the European Green Deal, the EU aims to produce net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The objective of RED II is therefore to support, and accelerate, the EU’s clean energy transition. A key policy of RED required that 20% of the EU’s energy consumption must come from renewable energy sources by 2020. Following the revisions in 2018, as well as subsequent revisions since, RED II now requires the EU to fulfil at least 42.5% of its total energy needs with renewable energy by 2030, with an aim of 45%.

Biofuels therefore play a key role in achieving the targets set out under RED II, whereby cereals and oilseeds can be used as a feedstock for their production.

Sign up to receive the latest information from AHDB.

While AHDB seeks to ensure that the information contained on this webpage is accurate at the time of publication, no warranty is given in respect of the information and data provided. You are responsible for how you use the information. To the maximum extent permitted by law, AHDB accepts no liability for loss, damage or injury howsoever caused or suffered (including that caused by negligence) directly or indirectly in relation to the information or data provided in this publication.

All intellectual property rights in the information and data on this webpage belong to or are licensed by AHDB. You are authorised to use such information for your internal business purposes only and you must not provide this information to any other third parties, including further publication of the information, or for commercial gain in any way whatsoever without the prior written permission of AHDB for each third party disclosure, publication or commercial arrangement. For more information, please see our Terms of Use and Privacy Notice or contact the Director of Corporate Affairs at info@ahdb.org.uk © Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. All rights reserved.