- Home

- Knowledge library

- Johne's disease

Johne's disease

Johne's disease, also known as paratuberculosis, is a chronic, contagious bacterial disease of the intestinal tract that primarily affects cattle, but is seen in other ruminant species, and rabbits.

The disease is caused by a bacterium called Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (M. paratuberculosis). It is characterised by a slowly progressive wasting away of the animal and increasingly severe diarrhoea.

Difficulties in controlling Johne’s disease arise from the three to five-year-long incubation period. This long duration between infection and clinical signs means it is hard to diagnose infection.

While only a small proportion of cattle will show clinical signs of wasting or scour at any one time, it is likely that a much larger proportion of the herd is infected and only showing very mild, if any, signs of the disease.

Most infections are acquired in the first few days of a calf’s life, through contamination of the environment or ingesting contaminated milk from an infected cow.

Calves are usually infected by ingesting a small amount of faeces contaminated with the disease, most commonly through dirty bedding, udders, teats or buckets.

Other potential infection routes include contaminated milk or colostrum if the dam is affected, or directly from the cow to the calf across the placenta during pregnancy. However, these two routes are less common.

Shedding of the bacteria in muck begins before clinical signs are noticeable, so these 'silent' carrier animals are important sources of transmission.

Adult animals that are exposed are much less likely to become infected, but Johne’s can be introduced to a non-infected herd through herd expansion or replacement animals that are infected with the disease.

Johne's disease has not been demonstrated as zoonotic. The organism that causes Johne's disease (M. paratuberculosis) has been found on occasions in patients with Crohn's disease, but no direct link between the diseases has been shown to exist.

The bacteria cause chronic inflammation of the intestines, characterised by diarrhoea, unthrifty animals and wasting, despite good appetite and normal body temperature. The inflammation of the intestinal walls makes them less able to absorb protein, leading to muscle wasting and low milk yield.

Because of the slowly progressive nature of the disease, clinical signs usually first appear from three years and older. The disease gradually becomes more and more severe, leading to malnutrition, debilitation and eventually death. In sheep, goats and other ruminants, diarrhoea may not be present.

As cows test positive before clinical signs begin to appear, we rarely see clinical signs as positive-testing cows are managed out of the herd in line with control strategies.

Other diseases such as lameness and mastitis, along with reduced fertility and milk production, may appear unrelated, but they can be attributed to underlying Johne's infection. For example, cattle that test positive for Johne’s disease are twice as likely to have a milk cell count higher than 200,000 cell/ml.

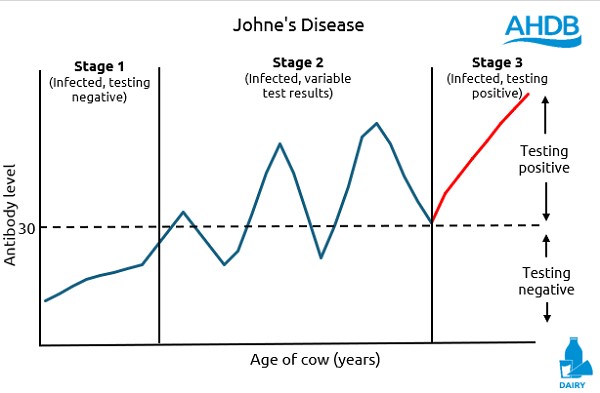

The single largest problem in Johne's disease control is the difficulty of detecting infected animals that are not showing signs of illness. They can be positive for Johne's, but the level of antibodies in the blood is not high enough to be detected by tests, as demonstrated by the graph below.

There are plenty of ways to test for Johne’s. You can look for antibodies in the bacteria in milk or blood, or bacterial DNA in faeces. New diagnostic tests are always being developed, but these methods are the most common at the moment.

Milk testing

Although testing can be carried out at a herd level on a bulk milk sample, it is not sensitive enough to detect animals in the early stages of infection and cannot give you any information about the infection status of individual animals.

Screening of individual milk samples is the most accessible and most common detection method. In the National Johne’s Management Plan (NJMP), samples must be taken from 60 random cows in the milking herd.

Herds with low levels of disease, or those wanting individual Johne’s status for breeding, culling or management decisions, may choose to use whole herd tests for closer surveillance.

Blood testing

Blood testing can be used to assess individual infection. However, blood and milk test results are not equivalent. If you are tracking prevalence via blood testing, you should not compare yourself to the national Johne’s Control Index which is based on milk testing.

Faecal testing

Faecal culture, although difficult and time consuming, will detect infected animals six months or more before they have developed clinical signs. It is more frequently used to confirm a positive milk or blood test in a high-value animal.

However it is important to remember that a negative faecal test does not mean that the animal is not infected, it just means that it was not shedding the bacteria in faeces at the time the test was taken.

If you test close to a TB test, you can find more animals testing positive for Johne’s. This is because the TB test stimulates Johne’s-infected animals to produce antibodies.

Animals not infected by Johne's remain unaffected, and test negative. In some circumstances it may be beneficial to schedule a Johne's test after a TB test, but this must be discussed with your vet.

We still advise that the herds leave a minimum of six weeks after a TB test before doing any Johne’s testing. This is achievable even if you are on 60-day TB testing. Your milk recorder will be happy to move the date of your milk recording if necessary.

You should wait a minimum of seven days after calving before doing any milk testing, including for Johne’s disease. This is because the amount of fat in colostrum makes it more difficult to run the test.

Johne’s disease cannot be cured, so once a cow is infected, it is infected for life. Preventing calves from becoming infected and avoiding buying in infected stock are the best long-term ways to control Johne’s disease in your herd.

Control involves good sanitation and management practices, including screening tests for new animals to identify and eliminate infected animals and ongoing surveillance of adult animals.

In herds affected with Johne's, calves, kids or lambs should be:

- Birthed in areas free of manure

- Removed from the dam immediately after birth

- Bottle-fed pasteurised colostrum (or tested disease-free colostrum), avoid pooling colostrum

- Raised separately from adults until at least one year old

For management of the wider herd:

- Use a simple method like putting a red tag in the ears of positive cows so you can easily differentiate them and manage them differently

- Do not calve positive cows in the same place as cows that have never tested positive

- Use Johne’s test results to make breeding decisions

- Avoid breeding replacements from positive cows

- Manage offspring from positive cows as high risk, even if they were negative at calving

These methods reduce the chance of disease transmission to the most susceptible population.

For control strategies on managing Johne’s disease, see the Action Johne’s website. All control strategies should be discussed and implemented with advice from your vet.

A well-informed and collaborative vet–farmer relationship is essential to disease management, and every farm is different, so your control plan should be bespoke to your situation and your needs.

To find your nearest BCVA-accredited Johne’s veterinary adviser (BAJVA), visit the Action Johne's website.

There is a vaccine against Johne’s disease, but it has limited efficacy. This is because calves are usually infected in the first few days of life, so they are already infected by the time they get vaccinated.

The vaccine does not prevent infection, and it cannot stop an infected cow from shedding the bacteria in her faeces and infecting others in the herd. However, it does extend the time before an infected cow shows clinical signs, so she has a longer productive life.

Vaccination should not be used as the sole control method. You should only vaccinate if you have planned a clear exit strategy with your vet and understand the implications of vaccinating.

Once a herd is vaccinated, it is difficult to tell whether an animal is infected because the tests cannot tell the difference between antibodies from infection and antibodies from a vaccine.

Testing for Johne’s changed on 31 March 2025 as the third phase of the National Johne’s Management Plan (NJMP) was implemented. Excellent progress in Johne’s management over the last few years means that previous benchmarks were out of date. These changes have been made by Action Johne's to allow more accurate tracking of disease incidence in the UK.

For more information on the National Johne’s management plan, visit the dedicated page on the Action Johne's website.