What could the EU-Mercosur trade deal mean for UK agriculture?

Thursday, 13 February 2025

After 25 years of negotiations, the EU and Mercosur have reached an agreement for a historic trade deal. The deal will see tariff reductions and quotas in key sectors as well as introducing mechanisms for tariff disputes. The deal still needs to be ratified by all member states and there has been agricultural opposition across France and Poland. In this article we explore the potential impact for the EU and the UK.

Key takeaways

- Beef sector: The deal would introduce a 99,000-tonne beef quota covering all Mercosur countries, on top of Hilton quota (58,000 tonnes).

- Pork sector: Mercosur would gain a 25,000-tonne tariff-rate quota (TRQ) for pigmeat over five years, with reduced tariffs on soybeans, potentially lowering EU pork production costs and enhancing EU pork’s competitiveness in the UK.

- Poultry impact: The deal would grant tariff-free access for 180,000 tonnes of Mercosur poultry to the EU, with Brazil’s lower production costs potentially impacting UK poultry exports and market share in the EU.

- Soy and feed grain dynamics: The removal of export taxes on soy from Mercosur is expected to reduce feed grain costs for both EU and UK producers, putting downward pressure on prices.

- Brazilian Real devaluation: The devaluation of the Brazilian Real makes Brazilian agricultural exports more price-competitive, boosting the competitiveness of South American products like beef and poultry in the EU, while making EU products comparatively more expensive.

Beef

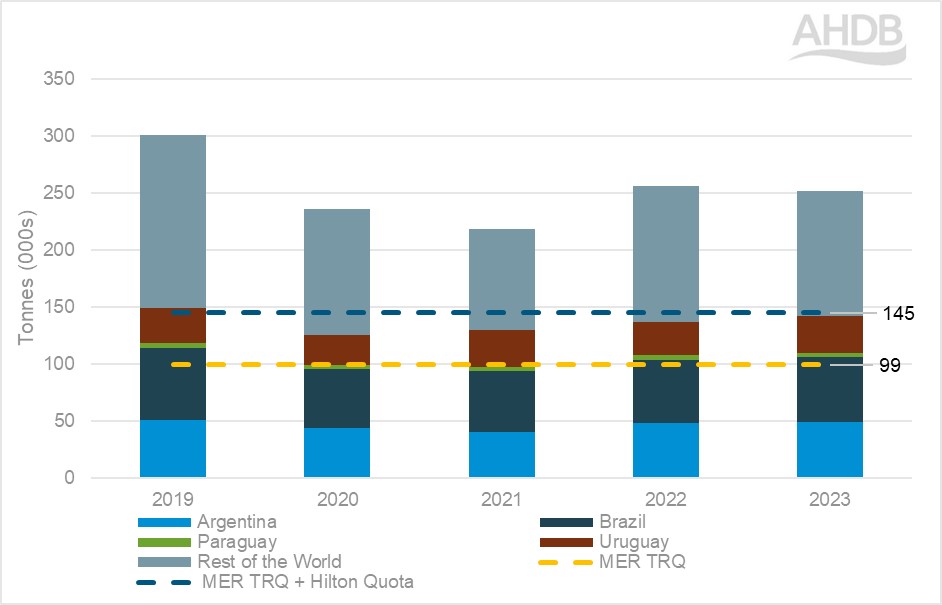

The deal negotiated for the EU retains the 2019 inward TRQ of 99,000 tonnes (carcass weight equivalent) with a 7.5% duty but extends its application to all four Mercosur countries instead of just Brazil and Argentina. The quota, divided into 55% fresh and 45% frozen meat, represents 1.6% of EU beef production.

In 2023, EU imports from Mercosur totalled 141,537 tonnes, exceeding the quota by 42,537 tonnes. There has been a 4.14% average annual growth rate in EU beef imports from Mercosur since 2021, despite disruptions from Brexit and COVID-19.

The Hilton Agreement, which permits 58,100 tonnes of premium beef imports into the EU from eight countries, including the four Mercosur nations, currently applies a 20% preferential tariff. The 2024 deal proposes removing this tariff for Mercosur exports while maintaining it for other countries, indicating likely revisions to future quotas.

Under the 2022–2023 Hilton quota, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay exported 29,500, 10,000, 5,600, and 1,000 tonnes respectively. Although Brexit and South American competition were thought to threat Irish beefs market share in the UK, we have not seen this, favourable post-Brexit terms ensured Irish beef accounted for 70.4% of UK imports in 2023, aided by a strong pound and high price differential.

Figure 1: Imports of fresh and frozen beef into the EU

Source: Trade Data Monitor

The UK, as a net importer of beef, primarily relies on domestic and Irish beef for its supply. However, it exports higher-value cuts to the EU, which remains a key market post-Brexit. The influx of competitively priced South American beef could depress prices in the EU, eroding demand for UK exports. Additionally, UK beef already faces regulatory checks and tariffs when entering the EU, and the preferential terms granted to Mercosur countries under the EU-Mercosur trade deal could further disadvantage UK producers.

Trends in EU beef imports show a decline in beef from the UK and an increase from the four Mercosur countries. If the trade deal is fully ratified, this trend is likely to accelerate, as preferential terms for the South American bloc come into effect. Furthermore, the UK may also see an increase in beef from the EU, as more price-competitive beef from Mercosur nations displaces the EU's domestic supply. However, any displaced beef from the EU entering the UK is expected to have a negligible impact on UKs domestic beef prices, given that the TRQ for Mercosur countries only represents 1.6% of EU production.

Pork

Under the potential trade deal, Mercosur countries will gain access to a TRQ of 25,000 tonnes of pigmeat into the EU, with an initial allocation of 4,167 tonnes in the first year, rising to 25,000 tonnes over five years. The in-quota tariff will be €83/tonne, significantly lower than the €536/tonne charged under the MFN tariff for fresh carcasses. Paraguay will also gain an additional 1,500 tonnes of access in 2024. Currently, Mercosur countries export negligible amounts of pork to the EU, but reduced tariffs could shift this dynamic, especially given the lower producer prices of Paraguay.

Mercosur nations are also major soy exporters, with Brazil alone accounting for 56.9% of global exports. While these countries impose export taxes on soy, a signed deal could reduce or remove these taxes, lowering feed costs for EU pig producers. Feed accounts for a significant portion of production costs and soya as a high protein crop is a key ingredient. Reduced soy prices would enhance the cost competitiveness of EU pigmeat. In 2023, EU pig production costs stood at £1.89/kg, compared to £1.96/kg in the UK.

Lower production costs in the EU, including cheaper feed, would likely make EU pork more competitive globally and within the UK market especially as there are no tariffs on pork entering the UK from the EU. The UK, which exported 41,730 tonnes of pork to the EU in 2024, may face increased competition from both EU pork, as EU producers benefit from cost advantages.

Poultry

The EU-Mercosur trade agreement would allow 180,000 tonnes of duty-free poultry into the EU, representing 1.4% of EU consumption. Currently, Mercosur poultry exports to the EU average 66,256 tonnes annually with 97% coming from Brazil. The UK exports average 224,527 tonnes. Brazil, the world's largest poultry exporter, has significantly lower production costs (£1,018/tonne) than the UK (£1,331/tonne).

Tariff removal will make Brazilian poultry highly competitive, potentially eroding UK market share in the EU. Additionally, reduced soy export taxes under the deal could lower EU poultry production costs further as imported soya places downward pressure on feed grains. This may displace some of the UKs domestic supply as cheaper poultry enters the country from the EU but is unlikely to cause disruption due to the rising demand and consumption for chicken meat in the UK.

Dairy

Mercosur, as a trade bloc, is largely self-sufficient in dairy production, with Uruguay at 281% self-sufficiency, Argentina at 132%, Paraguay at 103%, and Brazil at 98%. The proposed trade deal focuses on processed dairy products, including cheese, infant formula, and milk powders.

Currently, dairy imports into Mercosur are subject to tariffs of 28% (18% for infant formula). The deal proposes TRQs of; 30,000 tonnes for cheese, 10,000 tonnes for milk powder, and 5,000 tonnes for infant formula, with tariffs gradually reduced to zero. These TRQs would also apply reciprocally to EU imports from Mercosur, reflecting contrasting peak dairy production periods in the northern and southern hemispheres.

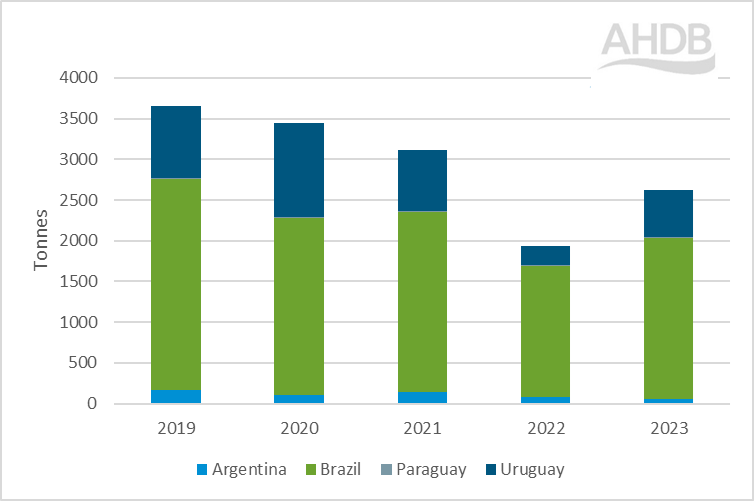

EU cheese exports to Mercosur have declined significantly, dropping from approximately 4,000 tonnes annually before 2020 to just over 2,500 tonnes in 2023. The TRQs are expected to rejuvenate the market for European cheeses, benefiting key exporters like France, Netherlands Italy, and Spain.

Figure 2: EU cheese exports to Mercosur

Source: Trade Data Monitor

The UK, if still part of the EU, would rank as the fifth-largest cheese exporter to Mercosur, with 410 tonnes exported in 2023. However, the deal will likely make UK cheese less price-competitive due the 28% tariffs still imposed on UK exports to Mercosur. Despite this, UK cheese may retain its appeal as a specialty product, providing some resilience compared to other sectors.

Soybean

As stated previously, there are currently no tariffs or quotas on soybean imports from Mercosur to the EU. However, countries within Mercosur impose export taxes on soy, with rates varying between countries: Argentina levies the highest tax at 33%, while Paraguay applies the lowest at 10%. The incoming trade deal could see these export taxes removed for soy destined for the EU. In 2024/25 marketing year soybean imports into the EU are coming from the US 48 %, Brazil 35.5 %, Ukraine 10.8 % and Canada 5 %.

The EU has also seen increased demand for imported soybean, in the 2024/25 season that started in July imports had reached 6.96 million metric tons by 5 January, compared with 6.22 million tons a year earlier. The deal may come at the perfect time for Brazil and the Mercosur countries who look to take advantage of this expanding market.

With access to cheaper soybean, a key high-protein ingredient used in animal feeds across sectors such as poultry, beef, sheep, and pork, EU producers may substitute soy for local grains that would typically be consumed. This substitution could displace EU-produced grains, including feed wheat and maize, which could have a knock-on effect on UK markets. As EU producers look for alternative markets to sell their excess feed wheat and maize, this could place downward pressure on feed wheat and maize prices in the UK.

On the flip side, UK producers in the red meat, poultry, and pork industries may benefit from the reduced cost of feed, as the increased supply of cheaper soy results in lower feed prices.

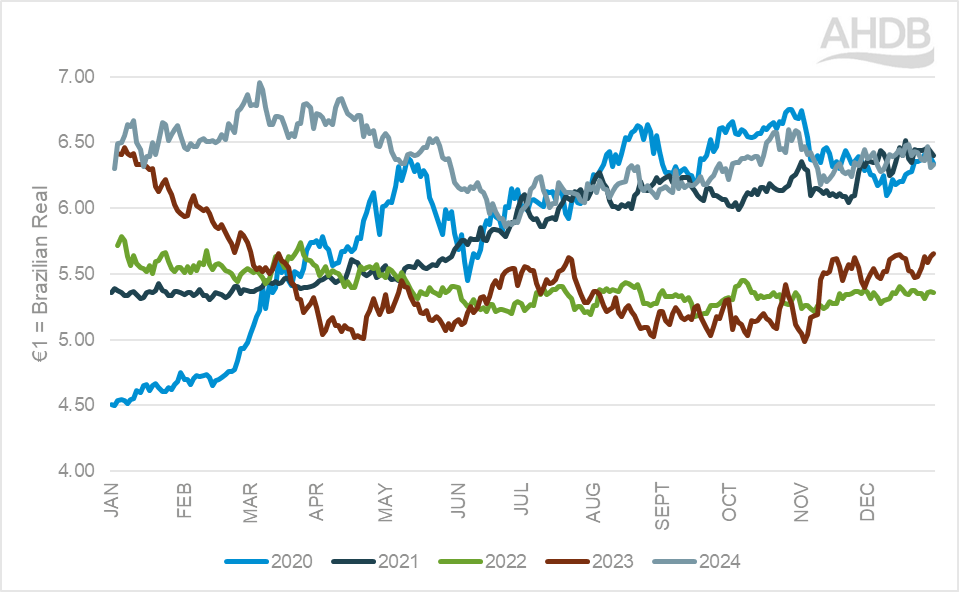

Brazilian Real

Brazil the largest economy of the 4 countries and largest agricultural exporter, has seen its currency the Brazilian Real (BRL) experience historic devaluation over the last 5 years, driven by inflation pressures. A weaker BRL enhances the competitiveness of Brazilian exports such as beef, poultry and reducing their prices for European buyers. This gives Brazilian agricultural products a price advantage, leading to increased competition in the EU market.

Figure 2: Exchange rate between Euro and the Brazilian Real (BRL)

Source: London Stock Exchange Group

Simultaneously, the the euro benefits UK buyers, as it makes imports from the EU more competitive. The stronger pound strengthens the purchasing power of UK farmers, enabling them to purchase cheaper cereals and oilseeds from the EU, with 77% of UK wheat and 44% of maize imports coming from the region. This trend is further supported by the rising value of the pound, which makes feed wheat and other agricultural products from the EU more affordable.

The potential EU-Mercosur trade deal, which includes reduced tariffs, and the removal of export taxes on soy, is expected to boost Brazil’s price competitiveness even further. The BRL's devaluation amplifies this advantage, making Brazilian agricultural exports more attractive to the EU. For the UK, this dynamic, along with cheaper Brazilian feed ingredients, is placing downward pressure on UK feed wheat prices, potentially challenging domestic producers.

While the UK benefits from cheaper imports, the broader impact of the devalued BRL and stronger sterling highlights the complex and evolving trade environment for UK farmers, particularly in terms of feed prices and export competition.

Environment

The agreement has drawn criticism for its environmental implications, particularly regarding deforestation and carbon emissions. Adding to these concerns is the one-year postponement of the EU Deforestation-Free Regulation (EUDR), raising questions about the EU's commitment to addressing these issues. While the deal includes a requirement to align with the Paris Agreement, critics wonder how much of this is substantive versus symbolic.

A notable feature of the agreement is its "rebalancing mechanism," which allows trade adjustments if either party fails to uphold environmental commitments. These measures are intended to protect vital ecosystems, such as the Amazon, while promoting sustainable trade practices between the regions.