- Home

- Knowledge library

- Minimising calving difficulties - Potential calving problems

Minimising calving difficulties - Potential calving problems

Below, we consider how to manage calving problems, including full breech and uterine prolapse.

Around 90% of calves that are dead after calving were actually alive at the onset of calving. This suggests most losses are preventable.

Watch our webinar for top tips on how to assist births and for guidance on resuscitating newborn calves.

Leg back

Calves commonly present with the head and one foreleg at the vulva. If this happens, the best option is to push the calf back, if possible. However, if the calf is large, or the cow is pushing hard, a vet may have to give an epidural injection to prevent her from straining forcefully.

To minimise difficulties:

- Lubricate the head and leg and push them back slowly. This will make it easier to reach the retained leg.

- Cup the foot with a hand to protect the uterus from sharp hoof edges and extend the leg through the pelvic canal.

- When both legs are at the vulva, apply calving ropes above the fetlock (wrist) joint.

Two people pulling on the calving ropes from both legs should apply slow, steady traction, or a calving aid can be used.

Head back

This often occurs when the calf is already dead.

When the feet are both presented at the vulva this can be mistaken for a calf coming backwards – check which way up the hooves are.

It may not be easy to lift the calf’s head up – normally this requires veterinary assistance.

After the vet administers the epidural, the forelegs can be pushed back as far as possible so as to reach the head. Then, with fingers in the mouth or eye socket, the head may be pulled straight and manipulated into the pelvic inlet.

If the calf is alive, it is preferable to get a head rope behind the ears and through the mouth (extreme care is needed) to help with the alignment and traction along the birth canal.

If this is not possible, misalignment of the head can be corrected by pulling the nose around, rather than the jaw.

If the head is pulled by the jaw, great care must be taken not to damage it.

Restrict the breeding period to nine weeks in spring-calving herds, so there are no stragglers, which can get too fat on spring grass and calve when there are fewer members of staff on hand to supervise.

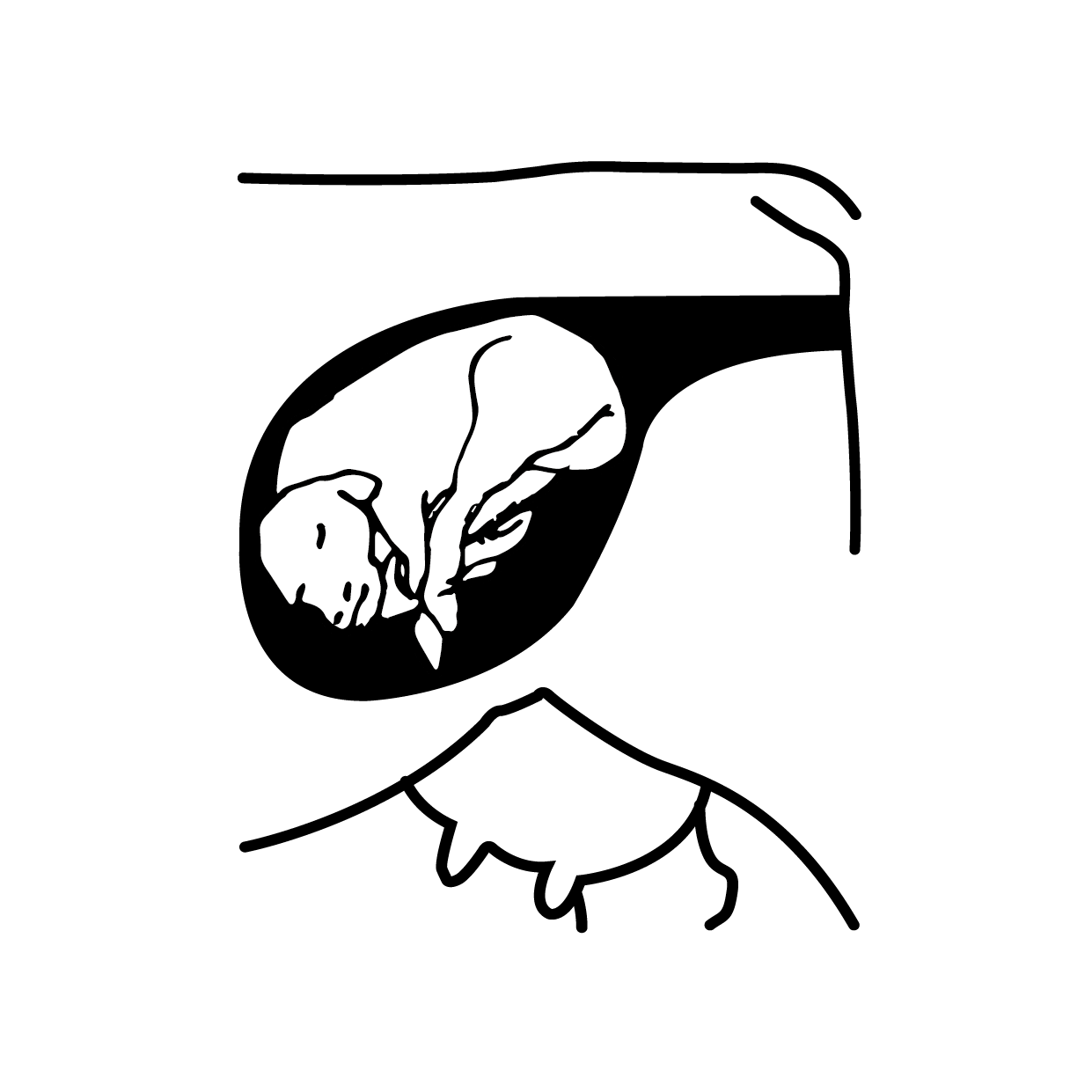

Breech (calf coming backwards)

Breech presentation is another common reason for dystocia.

Usually, two feet are seen protruding from the vulva – it is important to confirm that these are indeed the back legs (see graphic).

To deliver the calf safely, two strong people may be needed to pull slowly and steadily on calving ropes, or the use of a calving aid to apply traction.

If in doubt, call for veterinary assistance. If the calf gets stuck or is delivered too slowly, it may suffocate.

Possible complications from delivering a calf backwards are rib fracture and liver rupture.

Prolonged delivery can also compress the chest and blood vessels, including the umbilical cord, causing lack of oxygen to the brain.

Oversized calf

Calving problems caused by a relatively oversized calf are common in beef cattle.

When a large calf’s nose and feet are presented at the cow’s vulva, she may struggle to give birth on her own.

With two people pulling and reasonable traction, it should be possible to extend the front legs so that the fetlock is one hand’s breadth beyond the vulva, within 10 minutes of traction.

Seek veterinary assistance if greater traction is required or no obvious progress is made.

If the calf’s legs are crossed in the vagina or at the vulva, this can indicate that the shoulders are tight in the pelvis and veterinary assistance should be sought.

If the number of oversized calves is high, or is increasing, feeding and management should be reviewed, as well as bull selection.

Check the sire’s EBVs for calving ease, gestation length and birth weight.

Try not to calve cows with a BCS greater than 3.0.

Read our bull selection manual for details on what to look for when selecting a bull for breeding

Full breech

Full breech is when only the calf’s pelvis and tail are presented, while the back feet remain within the uterus.

The cow may not show signs of the second stage of labour, such as straining, because the calf does not engage with the maternal pelvis.

This means the problem can go undetected for a long period and the calf might die.

Subsequently, the cow may develop septicaemia or toxaemia and become very ill.

After administering an epidural injection to block the contractions, a vet may be able to push the calf back inside.

The hind feet need to be cupped and pulled towards the maternal pelvis and each joint extended in turn, before the calf is gently pulled out.

There is a risk that the umbilical vessels may rupture while trying to bring the hind legs around.

The uterine lining can also become damaged or even completely ruptured during extraction of the calf.

Two calves coming together

If the cow is carrying twins, they might try to be born together. In this case, it is necessary to identify which legs belong to which head.

This can be done by tracing back along the head and down the shoulder of one twin.

Put ropes on the correctly identified legs and, once the other calf is pushed back inside, the first can be pulled out slowly.

Only slight-to-moderate pressure is required to deliver a twin, which will be smaller than a single.

In most calving cases, it is easier to correct a malposition of the calf when the cow is standing because it can be pushed back or manipulated.

Once the presentation is corrected, it is fine to allow the cow to lie down. In fact, this is often the best position in which to deliver the calf because the pelvis is at its maximum diameter.

Hip lock

This occurs when excessive traction has been applied to an oversized calf and the calf’s hips become lodged as they enter the cow’s pelvis.

The cow will often be exhausted by this stage.

Veterinary attention is essential at this point because further traction, trying to roll the cow over or rotating the calf can cause nerve damage to the cow.

If the calf has died, it may have to be removed surgically.

Incomplete cervical dilation

Incomplete dilation of the cervix occurs occasionally in heifers, although the exact frequency is difficult to report because it is often confused with the early stages of labour.

Usually, the opening remains no more than 5–10 cm in diameter and does not dilate over time.

Natural dilation is achieved by the contractions of the uterus pushing the intact water bag through the cervix and into the vagina.

For animals in the early stages of first labour, manual pressure applied for 10–15 minutes may help to dilate the cervix.

In some heifers or cows, the vulva may also fail to dilate because of a lack of pressure from the water bag; veterinary attention may be required.

Human interference can disrupt the normal progression of labour. Ideally, leave cows and heifers undisturbed for four hours after mucus/slime is first seen at the vulva, unless the animal is clearly having powerful contractions every five minutes or so.

Uterine inertia

This usually occurs with older beef cattle with subclinical or clinical hypocalcaemia, where labour fails to develop past the first stage.

When the cow is examined, she is often fully dilated but the calf may be dead.

The cow might show other signs of hypocalcaemia (e.g. difficulty standing and low body temperature) and, if in the advanced stages, she is likely to be down and showing the typical ‘swan neck’.

Treatment involves administration of calcium borogluconate, available in either 20% or 40% concentrations.

It should be given intravenously, followed by oral supplementation of calcium via a drench or bolus.

Oral calcium given shortly before or after calving can prevent hypocalcaemia in high-risk cows, but veterinary advice should be sought beforehand.

In mild cases, once the hypocalcaemia is treated, it may be worth leaving the cow for a short time to allow the uterine tone to return and for her to progress naturally.

-1.jpg)

Treating cow with calcium boroglutanate

Credit: NADIS

Uterine prolapse

Cows that have had an assisted calving are at a higher risk of uterine prolapse, which is where the uterus is pushed out of the vagina.

This is a life-threatening emergency and requires urgent veterinary attention.

The cow should be kept quiet and, if practical, the uterus should be protected with a clean wet towel until the vet arrives.

Subclinical hypocalcaemia is another known risk for uterine prolapse and should be considered in all cases.

Uterine torsion

While uterine torsion is a relatively common problem, the exact cause is not clear.

Uterine torsion from 180° to 720° prevents the calf or fluids from showing at the vulva.

Often, there are no signs of the first stages of labour. The cow may isolate herself but the cervix will not dilate.

Occasionally a cow will appear to start calving and then stop and return to relatively normal behaviour.

On examination of the vagina, it is usually possible to feel a distinct twist, like a corkscrew – urgent veterinary attention is needed.

It is often possible to manually correct the twist but, because the uterus and cervix may be very fragile, caesarean section may be necessary to ensure delivery of a live calf and prevent injury to the cow.

If left undetected, the cow usually becomes very sick because of the death of the calf and development of a severe uterine infection.

Uterine ruptures and vaginal tears

Tears during delivery can allow submucosal fat to protrude or can lead to a more serious ruptured artery or vein.

The latter is life-threatening and needs urgent veterinary attention.

After any assisted calving procedure, examine cows to check that there is not another calf and that there have been no vaginal tears or ruptures.

Insert a clean, gloved and lubricated hand and feel for another calf, even after a large calf or twins.

Then run a hand around the pelvic area to feel for tears, holes or any pulsing fluid that might indicate a tear.

Uterine rupture and vaginal tears are more common when a calf has presented in the breech position.

If left undetected, the cow can appear normal for a few hours, but then become very sick very quickly, by which time treatment may be too late – the cow may die or have to be put down.

Further information

Find out how to minimise calving difficulties before breeding

Find out how to minimise calving difficulties during pregnancy

The information on these pages was compiled by Katie Thorley, AHDB Beef & Lamb and David Black, Paragon Veterinary Group and reviewed by Dr Alexander Corbishley, University of Edinburgh.

Topics:

Sectors:

Tags: