Economic Outlook - February 2023

Thursday, 9 February 2023

Updated 10 February 2023

The UK has narrowly avoided a recession. However, with zero growth for the three months to December 2022, it has entered an extended period of sluggish growth. Growth in Gross Domestic Product, (GDP), the measure of economic activity, shows the economy contracted by 0.5% in December., following growth of 0.1% in November. To be in a recession, an economy needs two successive quarters of negative growth, so for the moment at least we are not technically in recession. But is that merely semantics?

Inflation is also still raging. The Consumer Prices Index (CPI) rose by 10.5% in the 12 months to December 2022, down from 10.7% in November. Inflation is thought to have peaked in the UK and the slight drop in December was largely driven by a drop in fuel costs, although these were offset by increases in food and eating out costs.

Inflation has been driven to these dizzy heights through a combination of pent-up consumer demand following successive lockdowns and supply chain issues affecting the ability of manufacturers to respond to this demand. This was followed closely by the invasion of Ukraine and subsequent spikes in commodity prices, in particular energy.

The main issue with inflation is it drives down the rate of growth in an economy, hence the recession, and erodes households’ disposable income. This feeds through to more cautious spending patterns, further reducing economic activity and GDP. It is important to understand that as inflation subsides, it doesn’t mean that prices are dropping, rather that they have stopped rising. This means that peoples living standards, will take some time to catch up, depending on income growth. What this means for producers is that consumer confidence, along with demand will take some time to recover, despite inflation dropping, as it is expected to during 2023.

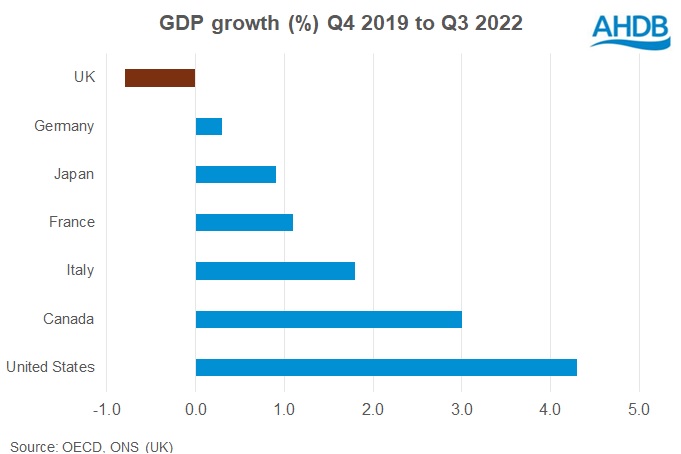

The pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine have caused huge economic problems on a global scale and are not unique to the UK. So why does the UK seem to have been affected worse than all the other G7 nations? The level of real GDP in Quarter 3 2022 is now estimated to be 0.8% below where it was pre-coronavirus at Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2019. Meanwhile, many of our European neighbours, as well as the US and Canada, have seen their economies recover to pre pandemic levels.

There are several factors underlying the slow recovery of the UK economy after the pandemic. First, the energy cap, which limited household bills, and subsequent lifting of that cap saw inflation surge in 2022. The response to the rapid increase in inflation was for the Bank of England to raise interest rates to dampen down demand. As of February 2023, interest rates in the UK were at 4.0%, compared to a rate of 3.0% from the European Central Bank, (ECB). The higher interest rates have inevitably led to higher costs of borrowing, further reducing consumers disposable income to a greater extent than the rest of Europe.

Secondly, the disastrous political turmoil that saw the short-lived Truss/Kwarteng minibudget added further to the chaos with turmoil in the financial markets and international confidence in the UK economy dropping swiftly. A quick change in leadership and a U-turn on many of the measures introduced by the former Chancellor restored stability but did mean interest rates were driven even higher by the loss of confidence.

There is also growing evidence that may be Brexit related. The UK labour market is incredibly ‘tight’ compared to many of its international counterparts. The loss of free movement of labour from the EU, which many sectors of the UK economy had relied upon for decades, is a major contributing factor. In addition, a large number of people of working age fell out of the UK labour market post-Covid, further tightening the market. Healthcare backlogs and Brexit’s effect on migration have impacted heavily on the labour market, causing well publicised bottlenecks in particular sectors.

In summary, 2023 looks set to be a year of economic unrest. The damaging effects of inflation, the supressed economic activity as a result of reduced spending power, and the lack of flexibility in the labour market will mean the hope that the UK would swiftly return to a pre-Covid ‘normal’ seems like a long-forgotten dream.