Economic Outlook – January 2022

Wednesday, 26 January 2022

What is economic forecasting?

Economic forecasting is not an exact science even in relatively normal times. Economics deals with the aggregated decisions of individuals, households, businesses and governments, so it is a living, rapidly changing and evolving entity, and as such lacks the comfortable predictability of say mathematics or physics.

The accepted wisdom is that economists examine the major economic variables like economic growth, the rate of inflation, unemployment, interest rates and exchange rates both domestically and globally and we determine what direction the headwinds are blowing and how hard. This means we can build a picture of the likely direction of travel of the UK economy. As a rule of thumb, the longer the time period of the forecast, the less accurate the predictions become, so outlooks and forecasts are constantly revised and updated.

Routinely across the globe there will be economic disruption caused by uprisings, war, politics or natural phenomena. These disruptions shock our economic systems sometimes globally and sometimes domestically depending on their cause, magnitude and proximity to the UK economy. Economic shocks upset forecasts as they are generally unexpected. Think the financial crisis of 2008, or the oil price shocks that reverberate across global economies, slowing growth and driving inflation.

Some economic upheavals can be expected and included in a forecast or modelling. AHDB assessed with some accuracy the possible implications of EU Exit for the UK agricultural economy. In our 2017 ‘Evolution’ scenario impact assessment, we outlined the consequences of leaving the EU single market with a full and comprehensive trade deal with the EU. This scenario foresaw a number of issues which have subsequently emerged: significant short-term disruption to the economy, especially for agriculture and trade in perishable goods, with increased trade friction for livestock products in particular, making exports to the EU more costly. We also expected labour shortages, due to the reduced quantity of EU labour flowing into the UK, first for growers and then for processors, food processing and food service. It is no satisfaction to be proved accurate when the disruption and the labour shortages, most recently in pig processing, have caused such pain both emotionally and financially across our industry. Other shocks are less predictable – like Covid-19.

2022 Outlook

So, what does 2022 hold for the UK economy? It is not only experiencing the aftershocks of EU Exit but also the massive impact of a global pandemic that is showing little sign of abating at the time of writing. The pandemic has been unusual in economic shock terms both in its speed of onset and its magnitude, as well as it’s uneven impact across the economy as a whole. The agricultural industry has been particularly hard hit in a number of areas. For instance, the loss of the food service market during the first lockdown affecting dairy farmers, or the staff absences compounding existing labour shortages in abattoirs and across food processing.

On a more positive note, the vaccine rollout has allowed the economy to reopen largely on schedule, despite continuing high numbers of coronavirus cases. The vaccines’ high degree of effectiveness, combined with consumers’ and businesses’ surprising degree of adaptability to public health restrictions, has meant that output this year has recovered faster than was expected back in March 2021.

More recently, the rate of transmission of the Omicron variant has taken the world by surprise. We have no way of knowing whether another new variant will sweep the nation, or the world, in the coming months, but we do know that this winter will be challenging for the industry. The Government stuck firmly to Plan B in order to avoid a full lockdown again, and lifted even these limited restrictions in late January. Even so, the ongoing rollout of the vaccine and boosters, the risk of vaccine-escaping variants, and the longer-term behavioural legacy of the pandemic remain key considerations for our economic outlook.

For these reasons we have, in this outlook, assumed, that the UK government will remain reluctant to impose further lockdowns, due to the impact on the economy, education and individuals, as well as the resistance from many key stakeholders, instead relying on the vaccine roll out and the potential for herd immunity to develop within the population.

This means it is likely that the economy will continue to recover during 2022. To examine what is likely to happen with the key variables, economic growth, unemployment and inflation, we will look at recent trends and then predict the likely direction of travel for the remainder of 2022.

Economic Growth

The latest data shows the first wave of the pandemic led to a 25 per cent fall in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from January 2020 to its trough in April, followed by a strong but fitful recovery over the remainder of last year as public health restrictions were successively loosened and then tightened. During the January 2021 lockdown, output fell by only 2.4 per cent in January, as consumer spending and business activity proved more adaptable to the restrictions than anticipated. From this higher starting level of output, vaccines and lifting of public health restrictions unleashed a stronger than expected rebound in demand. Latest data from the Office for National Statistics,(ONS) shows that the UK economy exceeded its pre coronavirus level for the first time in November 2021. On a quarterly basis, in the final three months of 2021 the UK economy will reach or surpass pre-Covid levels seen in the last quarter of 2019 if GDP grows by at least 0.2% in December and there are no downward revisions to figures for October and November.

The growth in GDP that took place in 2021 and is likely to continue through 2022 is largely making up for the pent-up demand and reduced spending during the pandemic. Growth will slow in 2022 as it will no longer be shored up by this rebound effect as the year progresses. In addition, the latest data from ONS only takes us to the beginning of the Omicron outbreak, and we can expect a sluggish start to growth as a result for these Winter months. The Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) has forecast overall GDP to grow by 6% in 2022, returning to more normal growth rates beyond 2022. The strength of the rebound in demand in the UK and internationally has led it to bump up against supply constraints in several markets. In the UK, these supply bottlenecks have been exacerbated by changes in the migration and trading regimes following Brexit.

Unemployment

The labour market has also proved more resilient than expected. The reopening of the economy has drawn 3.2 million workers off furlough since March 2021, leaving only 1.3 million on the coronavirus job retention scheme (CJRS) at its closure in September. ONS data shows the unemployment rate falling to 4.1% in the three months to the end of November, representing about 1.4 million people, down from 4.3% in the three months to the end of September. Demand for labour remains buoyant, with record levels of vacancies (more than 1.2 million in the three months to December). Average weekly earnings growth was 4.2 per cent in the three months to November, down from 7.2% in the three months to August. This means that with inflation rising, real wages will become stagnant or even fall in 2022. This will impact consumers who will feel their real incomes squeezed. However, some occupations are still seeing challenges with recruitment, particularly in the hard to fill vacancies like HGV drivers and some agricultural and food processing occupations, which is contributing to upward pressure on wages in these areas.

Inflation

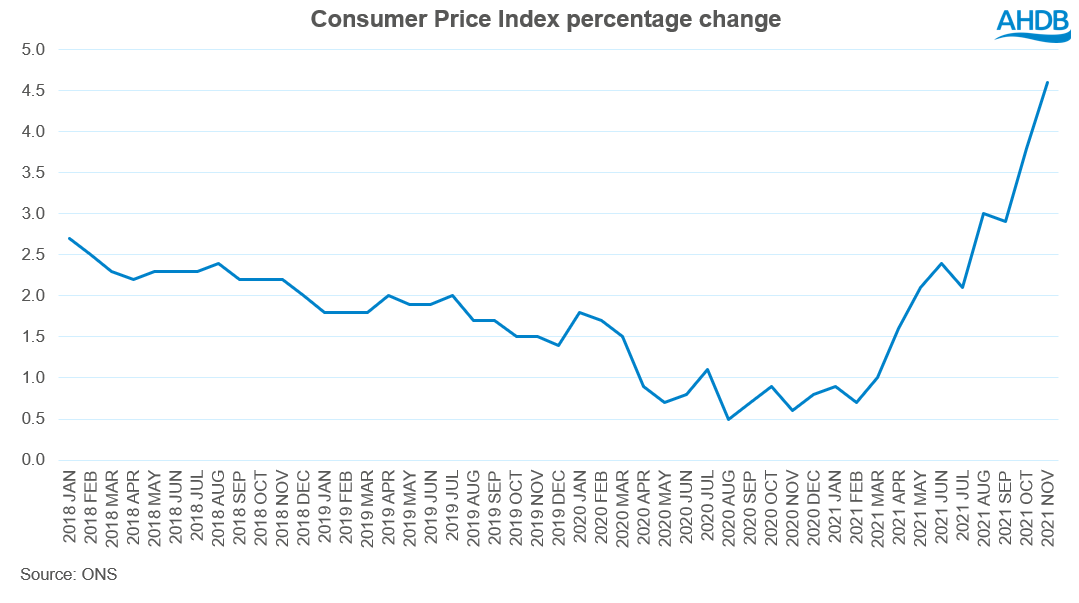

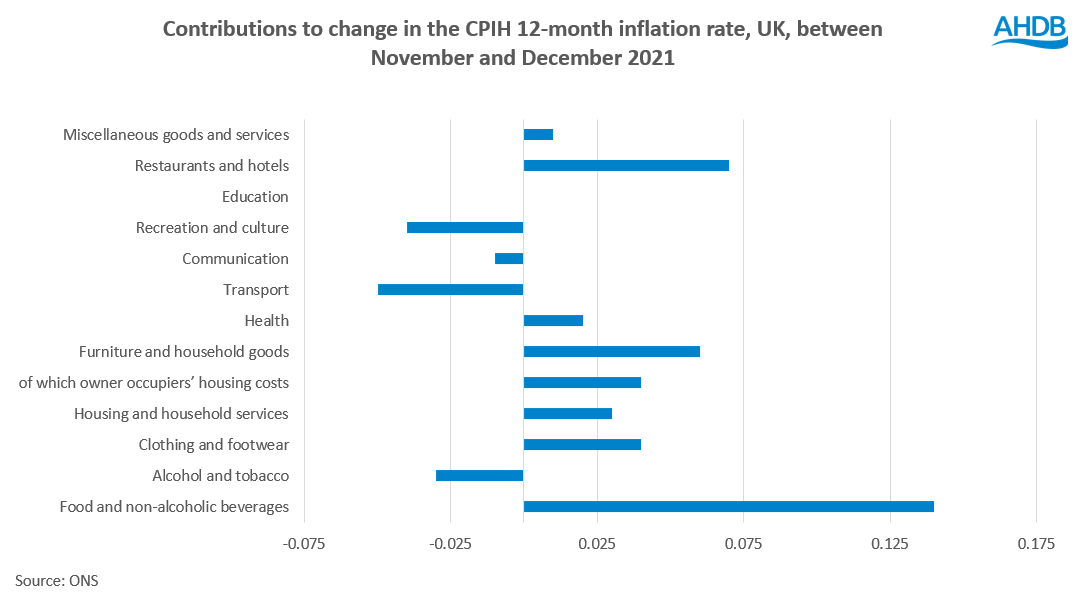

After remaining well below target during most of the pandemic, Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation has risen sharply in recent months, as the rebound in demand here and abroad has run up against supply constraints. Inflation reached 5.4 per cent in December 2021. Part of the recent increase can be attributed to the arithmetical effect on the annual comparison of unusually low prices a year ago. A wide range of prices contributed to the rise in the 12-month inflation rate, with the largest upward contribution to the change in the 12-month rate coming from food and non-alcoholic beverages, with eight of the nine food groups providing an upwards contribution. The rise also reflects increases in global commodity prices, which have raised fuel price inflation in particular. In addition, bottlenecks have emerged in several international product markets and there have been signs of shortages in some domestic markets too, adding to inflationary pressures.

In addition, energy prices have soared, transportation costs have risen and labour shortages have emerged in some occupations, in particular hauliers, abattoirs and meat processing, causing blockages in some supply chains. These can be expected to hold back output growth in the coming quarters, while raising prices and putting pressure on wages. The OBR predicts CPI inflation could hit the highest rate seen in the UK for three decades. The latest data seems to back this prediction. Inflation looks to be the biggest economic issue for 2022 and will drive the cost of borrowing, the cost of living, and have a knock-on effect on wage demands.

Inflation impacts real disposable income for consumers, and is likely to impact their spending patterns in 2022. Likely effects will be less eating out, trading down and being more price conscious when making purchases.

Conclusion

In summary – the economy shouldn’t be seen as emerging or recovering from Covid or EU Exit, but rather learning to live with them and adapting accordingly. Both events have led to the so called ‘scarring’ of the economy – those permanent changes that will slow down its ability to return to a pre-event ‘normal’. These factors can be seen clearly in agriculture both in supply chain management, with firms shifting from a just in time structure to build in more resilience, and also in consumer behaviour, working practices and consumption patterns. The economy looks set to reach pre-Covid levels and even exceed them by Q4 2021 or Q1 2022. However, the scarring will remain and there will be permanent changes to the way we work, socialise, buy goods and travel. Our market specialists and consumer insight team have examined the longer-term implications of these changes in this outlook.

Inflation looks set to be the big economic story for 2022. First driven by pent up consumer demand for big ticket items and durable goods built up during the various lockdowns, (so called delayed demand), it is now being exacerbated by energy prices which look set to soar in 2022. Increased consumer demand has led to bottlenecks in supply chains causing shortages in certain sectors and staff shortages in transport, food processing and food service, compounded by Brexit.

Inflation above 2% is widely regarded as damaging to economies. It reduces real incomes as prices rise, fuelling wage demands as workers strive to keep pace with the cost of living. It increases costs to businesses as their input costs rise, which impacts in particular those industries less able to pass on increased costs to consumers. For these reasons, interest rate rises are anticipated during 2022 as the Bank of England takes steps to curb excess demand and dampen down inflation.

Overall, it will be a year of recalibration as individuals and businesses adapt to a post pandemic, post EU exit environment. Adaptation is key. Those business who are ahead of the curve in examining the future direction of travel will be best placed to take advantage of new opportunities that arise in 2022. The landscape is changing rapidly for agriculture, in terms of economic drivers, policy drivers and our global trading environment. As always this creates opportunities, but also dangers for those unprepared. Waiting and seeing is a high-risk strategy. Prepare for this change by reading our in-depth analysis for your sector.

Topics:

Sectors:

Tags: